Resilient Real Estate this is the reason the poor and immigrants are being pushed out of Chicago to make space for people coming in from areas of the county destabilized by chronic resurgences of climate disasters.

If the poor don’t move out voluntarily with tax increases or buyouts, then looters and criminals are used to finish the job.

All those annoying festivals, sound stages, raised bike paths, and projects that don’t seem to fit into the old-style Chicago culture are marketing and pre-development infrastructure catering to new professionals moving into the city in the next 20-40 years.

Notice all those high-rise developments near main intersections on North Milwaukee Ave or added El stop on Lake and Damen, all meant to bring in urbanites from other cities.

As these new transplants get older and start having families, there will still be the traditional city neighborhood blocks with bungalows and multi-flat buildings.

There will also be a need to re-establish local manufacturing and service hubs throughout the city to counter the cost of shipping and logistics for consumer goods. Change is coming that will cause friction, triggering new opportunities for residents and small businesses.

—–

Climate is the Newest Gentrifying Force, and its Effects are Already Re-Shaping Cities

by Aparna Nathan

July 15, 2019

Bright blue water, white sand beaches, and all within feet of your front door: these features make beachfront properties in Miami some of the most desirable (and expensive) real estate in the city. But in 2017, Hurricane Irma swept through the city, causing billions of dollars in damage to these sought-after properties. Meanwhile, lower-income inland neighborhoods like Little Haiti and Liberty City were battered but somewhat protected from flooding and winds by their elevation and distance from the coast.

These neighborhoods have historically been seen as undesirable by real estate developers and affluent homebuyers. But their climate resilience may lead to an influx of real estate investment and spiking home prices as the changing climate starts playing a bigger role in determining where and how we live. This phenomenon, known as “climate gentrification,” will not only exacerbate inequality in cities already plagued by housing shortages and socioeconomic inequity, but also puts vulnerable populations right in the path of impending natural disasters.

In search of resilient real estate

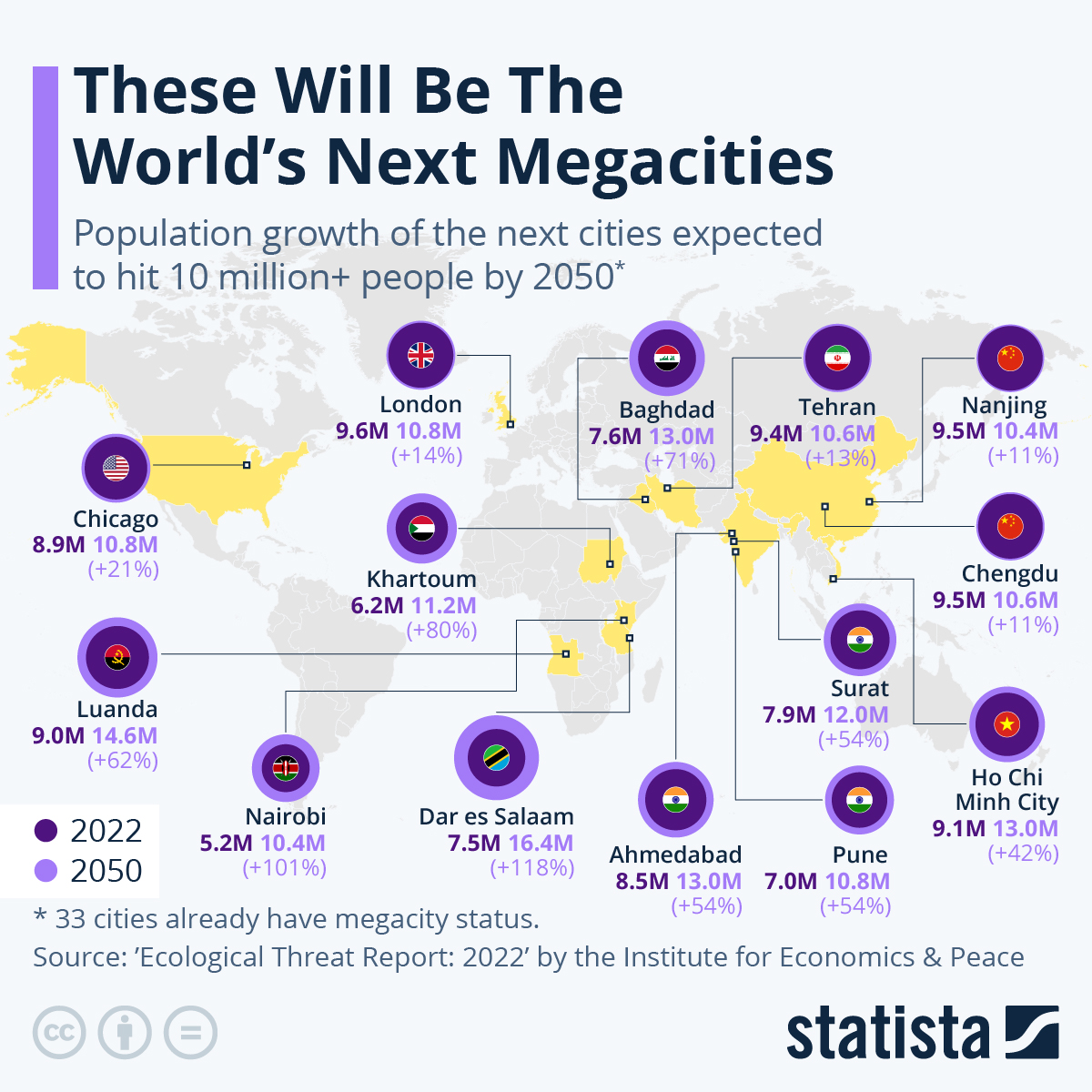

The World’s Next Megacities from Jan 2023 https://www.statista.com/chart/29152/the-worlds-next-megacities/

The term “gentrification” tends to evoke images of luxury condos rising from the rubble of public housing developments and the replacement of community-run businesses with high-end commercial real estate development. Officially, it is defined as the renovation of under-developed neighborhoods to make them suitable for more affluent residents, often resulting in the displacement of low-income people of color who can no longer afford to live in their homes.

But climate gentrification throws in an additional factor: the impending shifts in global climate as a result of carbon emissions. For example, warmer sea temperatures infuse hurricanes with more energy and higher wind speeds, making them more destructive. This has been reflected in the increasing frequency of Category 5 hurricanes—the highest possible rating on the Saffir-Simpson scale. And it’s not just hurricanes; other natural disasters like wildfires and tornadoes are also escalating. Rising temperatures in the West are causing snowpacks in the mountains—a major source of water for surrounding areas—to melt earlier, leaving the region drier for a longer period of subsequent time. As a result, wildfire season now extends for over half the year.

The prospect of purchasing a home that will be underwater or in the middle of a desert in fifty years is unappealing to homebuyers and makes weather-resilient neighborhoods more desirable. This means that homes protected from floods at higher elevations or far from wildfire-prone brush will increase in price, making them unaffordable for low-income homebuyers. This leaves already-vulnerable populations at the mercy of life-threatening weather events.

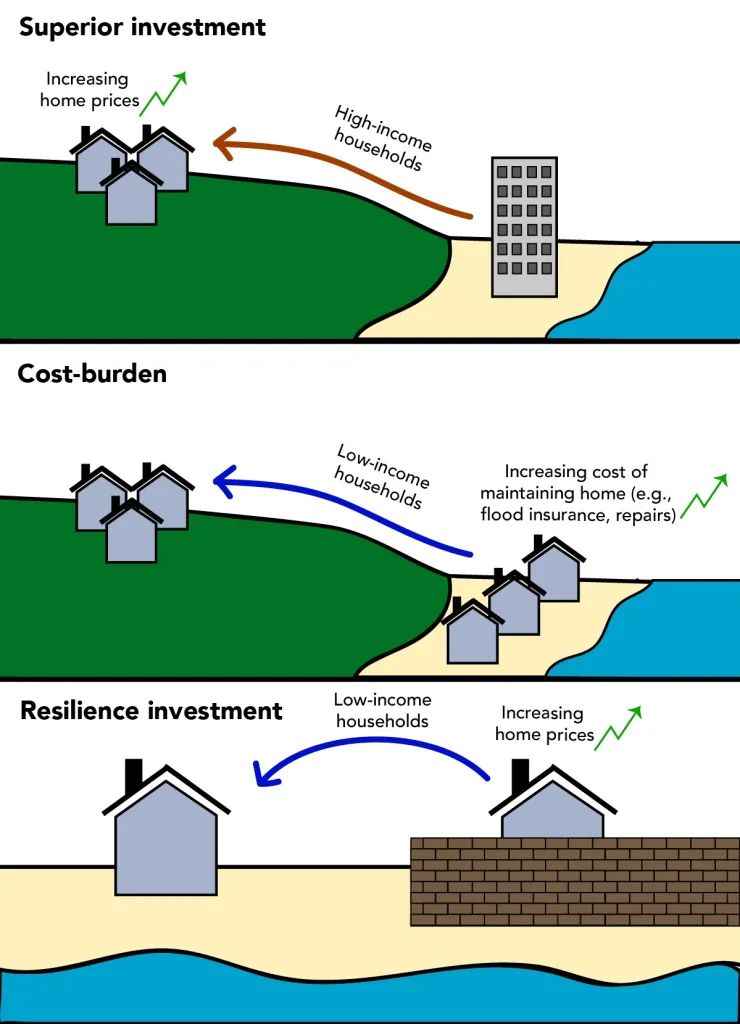

Figure 1: Climate gentrification. A 2018 study from Harvard University proposed three examples of mechanisms by which climate gentrification occurs, depending on the area in question. Some regions are susceptible to the “Superior investment” mechanism, where climate-resilient properties are more desirable, so their prices increase and only high-income households can afford them. Other regions face the “Cost-burden” mechanism, where less resilient neighborhoods are inaccessible to low-income people who cannot afford the expenses associated with natural disasters. Finally, “Resilience investment” occurs when a neighborhood has climate resilience infrastructure, which makes it more expensive.

Figure 1: Climate gentrification. A 2018 study from Harvard University proposed three examples of mechanisms by which climate gentrification occurs, depending on the area in question. Some regions are susceptible to the “Superior investment” mechanism, where climate-resilient properties are more desirable, so their prices increase and only high-income households can afford them. Other regions face the “Cost-burden” mechanism, where less resilient neighborhoods are inaccessible to low-income people who cannot afford the expenses associated with natural disasters. Finally, “Resilience investment” occurs when a neighborhood has climate resilience infrastructure, which makes it more expensive.

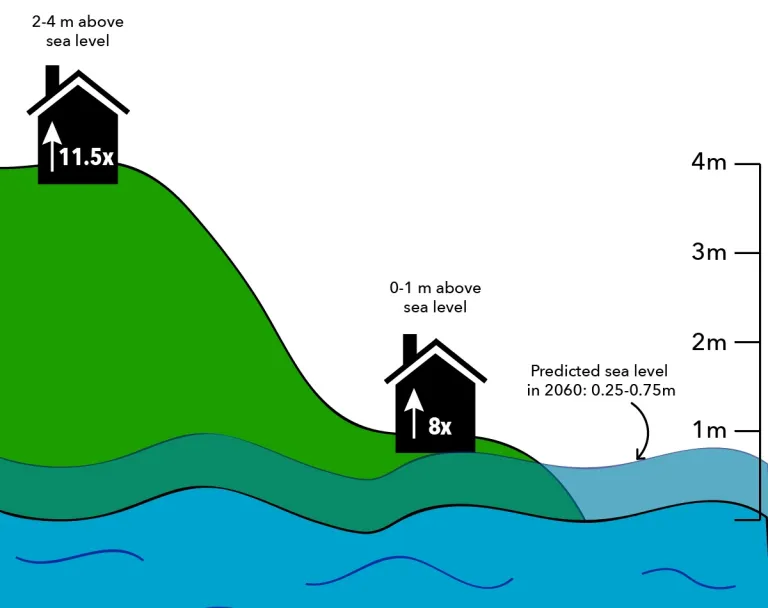

The term “climate gentrification” was first explored comprehensively in a 2018 study about housing prices in Miami-Dade County. This hurricane-prone region has been a closely studied example of resilience and recovery in response to climate change and natural disasters. In the study, they described three different forms of climate gentrification (Fig. 1). First, low risk of weather damage can make low-income neighborhoods more attractive, spurring the migration of wealthy homebuyers into these areas. Second, and conversely, living in areas with high risk of weather damage requires expensive personal investment into weather-proofing measures. These investments are typically infeasible for low-income households, which forces them to leave. Third, areas in which community investments have already improved resilience (e.g., storm drains, flood walls) are more desirable and become inaccessible to low-income families. Miami falls into the first category. In the study, the authors found that, in coastal neighborhoods that are more exposed to the ocean, home prices are increasing more rapidly in areas at higher elevation (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: The impact of climate on housing prices. In the 2008 Harvard study of climate gentrification in Miami Dade county, they found that home prices were increasing in most neighborhoods, but areas at higher elevations saw larger increases (11.5x at 2-4 m above sea level, compared to 8x at 0-1 m). In fewer than 50 years, areas less than a foot above sea level are predicted to be underwater.

Figure 2: The impact of climate on housing prices. In the 2008 Harvard study of climate gentrification in Miami Dade county, they found that home prices were increasing in most neighborhoods, but areas at higher elevations saw larger increases (11.5x at 2-4 m above sea level, compared to 8x at 0-1 m). In fewer than 50 years, areas less than a foot above sea level are predicted to be underwater.

Another similar study looked nationwide and combined home price data from Zillow with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s predictions of sea level rise. They calculated that homes that are at risk of flooding due to rising sea levels sell for 7% less than homes equidistant from the waterfront that are not at risk of flooding. This might seem like common sense, but to track down the exact cause, researchers have interviewed homebuyers in flooding-prone areas, like the Jersey Shore. There, they found that an area’s reputation for flooding makes homebuyers less likely to pay as much as they normally would, especially since they will often have to bear the extra expense of getting flood insurance.

Flooding is only one way that nature dictates where people can live. Further from the Atlantic coast, other forces are at play. In California, wildfires are becoming more common and forcing people to move, in some cases because their homes were destroyed, and in others because the threat of fire makes it difficult to get insurance or a mortgage. Los Angeles, in particular, may see an influx of people from the coast (as sea levels rise) and further inland (as fires rage) into its traditionally working-class Eastside neighborhoods. And although the Great Lakes have been touted as the climate-proof region of the future, recent deep freezes and flash floods demonstrate that the Midwest is not immune to extreme weather.

Fighting gentrification with policy

Climate gentrification may seem inevitable: the climate is changing, and in combination with the human instincts that drive real estate prices, it seems like it may be—somewhat ironically—the perfect storm. But local government policies can play a role in blocking such inequity or exacerbating it. For example, improving public infrastructure can make a city more resilient to weather events. The city of Galveston, Texas, built a 10-mile-long seawall and raised the city above flood level with 16 feet of sand, and in 2002, Florida passed a building code that requires buildings to be able to withstand 111 mph winds. Other strategies include improving drainage in asphalt-carpeted cities and increasing the distance between homes and flammable fauna to minimize the spread of wildfires.

But these are not cheap endeavors, and as municipal infrastructure projects, the natural funding source is taxes. Rising taxes would also burden the low-income populations that would be displaced by climate gentrification, however, so some cities look to other sources of income—like tourism or bonds—to finance climate resilience measures. As one of the cities most urgently facing the repercussions of climate change, Miami has taken the first steps among its peers to keep natural disaster-prone neighborhoods safe. The city recently agreed to use its income from the Miami Forever Bond to support flood-proofing infrastructure, like water pumping stations and better drainage systems, and to make homes more resilient. Local advocates are working to make sure that these funds go toward both affluent and low-income neighborhoods; otherwise, there’s a risk of pushing these neighborhoods down the “resilience investment” pathway of climate gentrification, where the increased infrastructure makes certain neighborhoods more desirable and unaffordable. The city has also commissioned research to quantify the effects of climate gentrification on its neighborhoods so that it can implement further evidence-based policies.

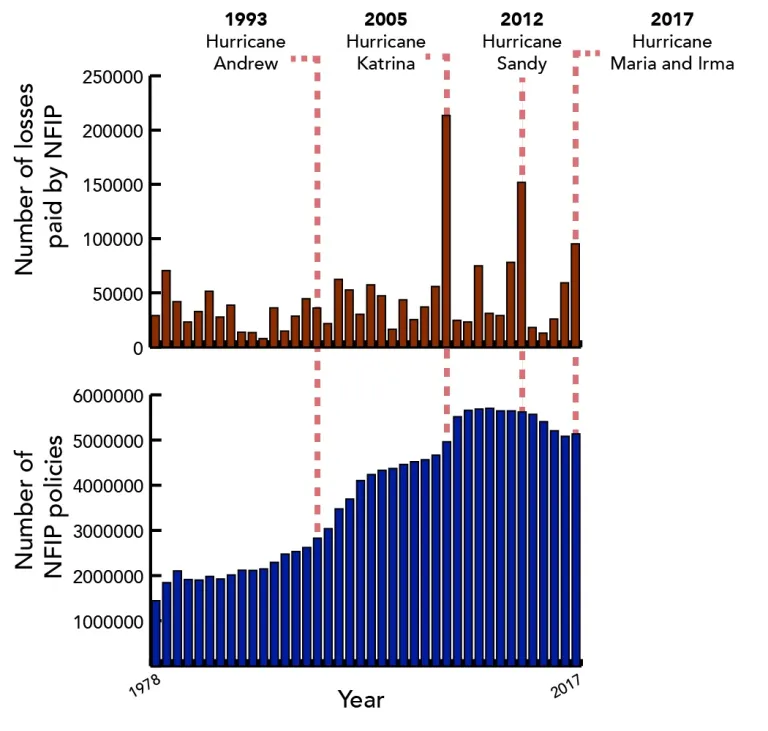

One area in which such policies could be instrumental is with regards to flood insurance premiums. Homes in high flood-risk areas that are purchased with the assistance of federally regulated mortgages are legally required to have flood insurance (Fig. 3). As the flood risk increases in low-income coastal neighborhoods (as has been happening in Florida and New Jersey, for example), the added expense of the insurance premium may make these neighborhoods unaffordable, increasing the rate of climate gentrification.

Figure 3: Dramatic weather events impact flood insurance. Increasing numbers of homes have acquired flood insurance over the past four decades. This has happened in parallel to the increasing frequency of highly damaging hurricanes, resulting in hundreds of thousands of insurance claims through the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP).

Figure 3: Dramatic weather events impact flood insurance. Increasing numbers of homes have acquired flood insurance over the past four decades. This has happened in parallel to the increasing frequency of highly damaging hurricanes, resulting in hundreds of thousands of insurance claims through the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP).

In the wake of a particularly damaging year in 2017, the National Flood Insurance Program increased premiums by 8% on average for 2018 and 2019, and the Federal Emergency Management Agency announced the adoption of a new system for evaluating properties’ flood risk. Beginning in 2020, this updated “Risk Rating 2.0” will be used to re-assess insurance premiums that have traditionally been determined based on other factors, not direct risk of flooding. This will reduce some properties’ premiums, while increasing them for other properties, potentially making the expense of maintaining flood-prone properties untenable in low-income communities. Some congressional representatives are working to develop a program that discounts the rate for low-income homeowners.

Housing is just one example of an overarching theme arising in the arena of climate change activism: as the climate changes, it will be easier for those with more resources to adapt. The increase in home prices in weather-resilient neighborhoods shows that climate gentrification is already having a measurable impact. It is disrupting communities and widening socioeconomic gaps. Many researchers are working from a scientific angle to understand what is causing the increasingly wild weather events, and how we can better predict them and protect ourselves. Atmospheric scientists are studying the origins of Category 5 hurricanes and engineers are designing climate-proof city infrastructure. This kind of work is crucial to improve our response to natural disasters. But recent examples of climate gentrification show that there is also important work to be done to understand the social impact of these events and how weather can work synergistically with other socioeconomic forces. These dual approaches will be essential to keep cities and neighborhoods resilient for everyone.

Aparna Nathan is a third-year Ph.D. student in the Bioinformatics and Integrative Genomics program at Harvard University. Follow her on Twitter at @aparnanathan

———-

The World’s Next Megacities

Megacities

by Anna Fleck,

Jan 19, 2023

By 2050, 70 percent of the world’s population will live in cities, up from 54 percent in 2020, according to a new report by the Institute for Economics & Peace. This increase is being driven by both population growth and a continued shift towards urbanization, particularly to so called ‘megacities’ – metropolises that have a population of 10 million or more.

Urbanization takes place because of both push and pull factors. The IEA describes how in the Democratic Republic of Congo’s capital of Kinshasa, factors pushing people away from rural areas include issues of violence and a general lack of security, the presence of criminal groups, lack of policing, ecological degradation, and the fact there are too many people for the available agricultural land. Meanwhile, a pull factor could be the attraction of an increase in the standard of living.

There are currently 33 megacities worldwide. Tokyo (37.3 million), Delhi (32.3 million), Shanghai (28.7 million), Dhaka (22.6 million), São Paulo (22.5 million) and Mexico City (22.1 million) take the lead as the most populous of these. By 2050, 14 more cities are set to join their ranks, with a total increased population of some 213 million people. The new order will then become Delhi (49.6 million), Dhaka (34.6 million), Tokyo (32.6 million), Cairo (32.6 million) and Mumbai (32.4 million).

In addition to a rise in the number of people living in these cities, the countries themselves will also likely see economic growth. According to AXA, Manila in the Philippines and Bangalore in India are expected to see close to 150 percent GDP growth by the end of the decade.

Africa is the only world region expected to still see strong population growth by the end of the century, according to the Pew Research Center, while all other regions’ growth rates will start to tail off. This is reflected in our chart, as it’s notably the African megacities that will see the biggest population rate increases. Meanwhile, only three megacities will see decreases in their population size: the Russian capital of Moscow (-3 percent), and Japan’s Osaka (-12 percent) and Tokyo (-12 percent). Despite Tokyo’s shrinkage, brought on by an aging population and declining birth rate, the capital will still rank as the world’s fourth most populated megacity in 2050.

The 33 cities that have already hit megacity status are the following: Delhi, Dhaka, Cairo, Tokyo, Mumbai, Shanghai, Kinshasa, Lagos, Karachi, Mexico City, São Paulo, Beijing, Kolkata, New York City, Manila, Lahore, Bangalore, Chongqing, Buenos Aires, Osaka, Hyderabad, Tianjin, Guangzhou, Los Angeles, Rio de Janeiro, Bangkok, Jakarta, Shenzhen, Lima, Paris and Moscow.

It’s important to note here that different sources cite different statistics, and that especially with forecasts, situations can change. For instance, where the United Nations initially predicted that India would overtake China as the biggest country in 2027, it is now expected to take place in April of this year. In terms of megacity status, according to UN data from 2018, several additional cities, including Kuala Lumpur in Malaysia and Wuhan in China, will make the roundup even by 2035. https://www.statista.com/chart/29152/the-worlds-next-megacities/

———-

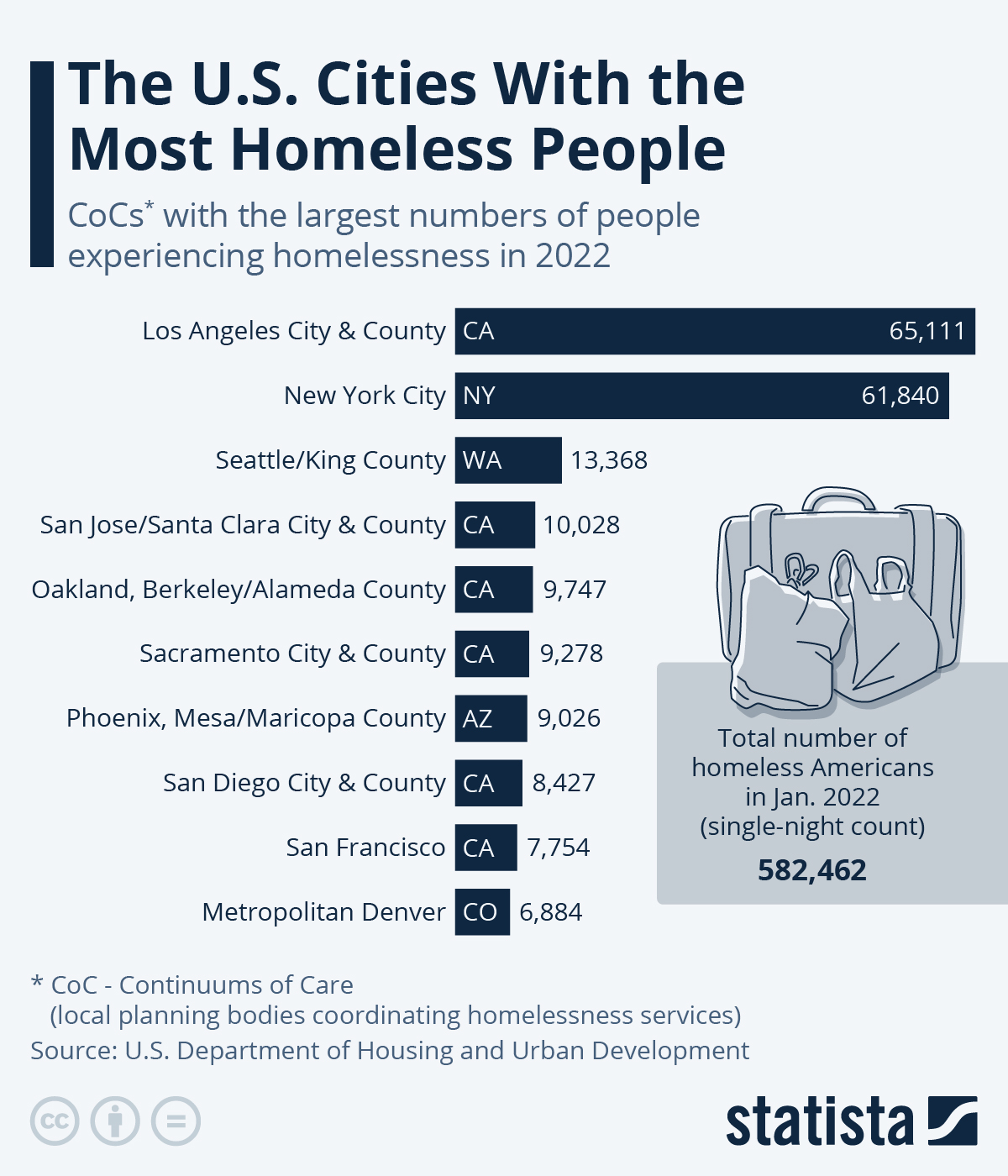

The U.S. Cities With the Most Homeless People

The U.S. Cities With the Most Homeless People

by Katharina Buchholz,

Mar 7, 2023

Over half a million Americans are currently homeless. After a period of progress and decline, the U.S. homeless population has increased slightly in 2020 and 2022, according to a report from the Department of Housing and Urban Development. The 2021 numbers were affected by shelters lowering capacity due to the Covid-19 pandemic during the count that takes places in the first month(s) of every year. It now stands at 582,462 individuals with two thirds living in shelters. While the number of sheltered individuals in 2022 approached the 2020 pre-pandemic level again, the increase in the nation’s homeless is primarily due to a rise in the unsheltered homeless population.

Around half of all unsheltered homeless people in the U.S. are located in California. The rates of unsheltered homeless populations are also high in other states on the West Coast. Tent cities are common occurrences in these states as a result of the growing unsheltered homeless populations. This very visible symptom of homelessness has proven divisive, and while some cities have embraced designated areas for camping as a solution for unsheltered people, others have recently cracked down on encampments, for example Sacramento, San Jose and Oakland.

Half of the U.S. homeless population is scattered across the country’s 50 biggest cities and their surrounding areas. 22 percent of them live in just two cities – New York and Los Angeles. Despite its considerable homeless population, New York has a very low rate of unsheltered individuals: only 5.4 percent lived on the streets in early 2022, which is in part due to the two cities opposing climates. In California 67.3 percent of homeless people were listed as unsheltered at the same time.

The CoCs for New York and Los Angeles – so-called Continuums of Care or local planning bodies coordinating the response to homelessness – saw around 62,000 and 65,000 homeless people in the early 2022 count. Other CoCs in the U.S. experiencing a high level of homelessness are Seattle/King County with around 13,3000 homeless people registered as part of the count, and San Jose and Santa Clara in California with more than 10,000. Out of the 10 CoCs with the biggest homeless populations registered in 2022, six were located in California.

https://www.statista.com/chart/6949/the-us-cities-with-the-most-homeless-people

Cover image: “Might be a while…” by nuttyxander is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 For more information:

A three-part series (accompanied by a video) in The Root explores the effects of climate gentrification on Little Haiti, and the activist forces combating it. https://www.theroot.com/tag/color-of-climate

The New York Times explains what makes some cities “climate refuges:” cities that anticipate evading the effects of climate change (spoiler: head north and inland). https://www.nytimes.com/2019/04/15/climate/climate-migration-duluth.html

Climate-driven migration is not new, and this Rolling Stone article reflects on how we can learn from past cases to forecast how migrations may shape our future landscape. https://www.rollingstone.com/politics/politics-news/welcome-to-the-age-of-climate-migration-202221/

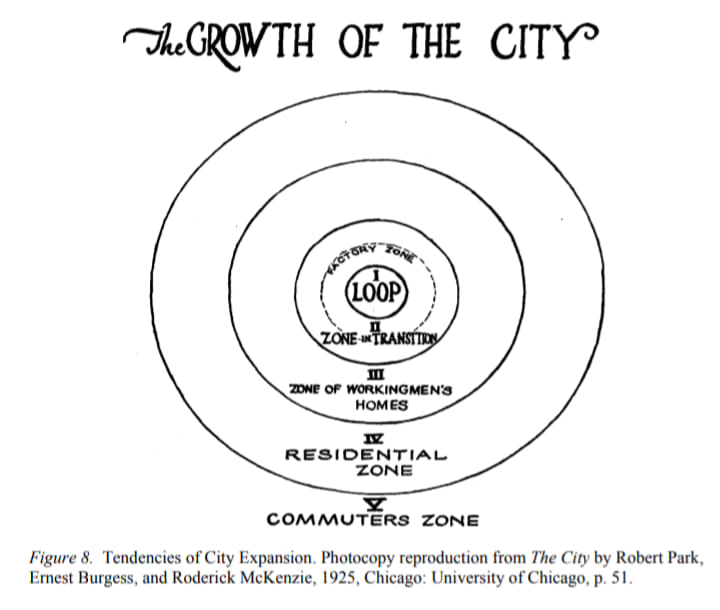

the City by Robert Park, Ernest Burgess, and Roderick McKenzie (1925) a trailblazing text in urban history, urban sociology, and urban studies.

the City by Robert Park, Ernest Burgess, and Roderick McKenzie (1925) a trailblazing text in urban history, urban sociology, and urban studies.

Its innovative combination of ethnographic observation and social science theory epitomized the Chicago school of sociology.

https://books.google.com/books?id=cOnH6O3CvXgC&pg=PP6#v=onepage&q&f=false